Archived Nihonto.ca (Yuhindo.com): Gassan Sadakatsu

Gassan Sadakatsu

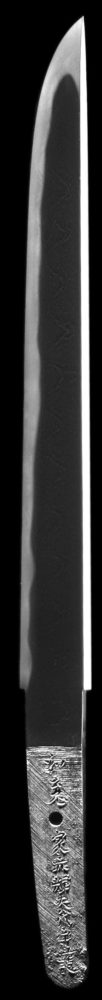

| period: | Gendaito |

| nakago: | ubu, one mekugiana, 9.7cm slightly curved |

| nagasa: | 22cm |

| hamon: | nie deki, ko-notare mixed with gunome |

| jigane: | ayasugi mixed with ko itame, with chikei, yubashiri and well displayed ji nie |

| sori: | 0cm |

| motohaba: | 2.5cm |

| kasane: | 6.06cm |

| price: | N/A |

Gassan 月山 is the name of a mountain in Ushu (the second character is the kanji for mountain), and this gives the old Gassan school of the koto period its name. The Gassan smiths made swords in a remarkable style in which the jihada appears as a series of rolling waves, called ayasugi hada. It is breathtakingly beautiful and is considered the key kantei point in identifying works of this school.

Though Gassan starts in koto, and there are smiths of this school in the Shinto period, it is not until the late Shinshinto period that the school begins to rise to its zenith.

At the beginning of the Shinshinto period, the grand-master Suishinshi Masahide had travelled the country encouraging swordsmiths to return to the work styles of the koto greats of old. In the revolution in technique that followed, Masahide accumulated many students of great skill. Among these students was Gassan Sadayoshi.

While Sadayoshi did not have the skill of Masahide, he sired a son who began working as a swordsmith at 14 years old, and was regarded as highly skilled at 20. He took the name of Gassan Sadakazu, and went on to become one of the true masters of his time.

In 1869 Osaka, the son of Sadakazu was born and set on the path of his talented father and eventually took the name Gassan Sadakatsu. Soon after taking up a hammer, the son like the father became considered a genius swordsmith, capable of working in all classical traditions with a high degree of skill.

Sadakazu had been appointed an Imperial Court Artist in 1906, and died twelve years later in 1918. Towards the end of his father and teacher’s life, Sadakatsu often made daimei and daisaku works. As their level of skill and their styles were nearly identical, it has been concluded that it is impossible to determine whether a particular sword is only daimei or whether it is actually daisaku. That this is impossible shows how well the student inherited his father’s skill.

After the death of Sadakazu, Gassan Sadakatsu in turn made swords for the imperial household, other dignataries, and shrines. During this period (the 1940s) Kurihara Hikosaburo ranked over 400 of the working swordsmiths of the time, and included Gassan Sadakatsu in the first rank (Sai-jo Saku, a rank including the top twelve of these 400).

As well as having inherited his father’s talent, Gassan Sadakatsu also proved to be an excellent teacher. His son Gassan Sadaichi (also read as Sadakazu II), and his student Takahashi Sadatsugu went on to become Living National Treasures. This designation by the Japanese government is the most prestigious one can receive, as it considers that the essential and highest cultural qualities of Nihonto are embodied in the recipient.

Gassan Sadakatsu Mamorigatana

-

昭和十四年Showa ju yon nenShowa 14 (1939)

-

十二月吉日Ju ni gatsu kichi jitsuA Lucky Day in the 12th Month

-

月山貞勝作Gassan Sadakatsu saku (kao)Gassan Sadakatsu made this (his seal)

-

和魂家亦輝夫氏守護Wakon Iemata Teruo shi syugoTo safeguard the Japanese Spirit of Mr. Teruo Iemata

Gassan Sadakatsu is one of the true luminaries of the 20th century group of Japanese swordsmiths. Because Sadakatsu was a virtuoso, today we find his work in all of the classical styles. The tanto shown here today is, in my opinion, in the style that is most precious since it shows the trademark ayasugi hada of the old Gassan school.

The signature dates this blade to 1939, which is four years before he died. It is chumon-uchi, that is, it was specially ordered and made for a customer, Mr. Teruo Iemata. The omotemei indicates that this tanto is what is known as a mamorigatana.

Historically in Japan, the sword has been regarded as being imbued with a kami, a soul or spirit that amongst other things has power over evil spirits, bad luck, and ghosts. Children were sometimes given tanto, known as mamorigatana, that were meant to protect them in a spiritual sense from these various evil omens. As time went by, the practice extended to women and men (such a mamorigatana could serve two purposes, guarding the owner in a physical as well as a spiritual sense). Even today, the gift of a tanto can be something regarded to protect and safeguard a loved one.

The word Wakon is a short form for Yamato Tamashii 大和魂. It is translated as “Japanese Spirit” and refers to the traits of valour, honor and refusal to accept defeat. In these translations, sometimes the meaning is somewhat lost in the words chosen, since on our side of the language divide they may come loaded with their own cultural connotations. To get an idea of the meaning of this word, we can turn to the phrase “Bushi-no-tamashii” which was used to refer to the Japanese sword as the “soul of the warrior” or as we commonly refer to it now, the soul of the samurai. So it begins to take shape that this tanto was intended to symbolize and protect the highest spiritual ideals for Mr. Iemata, and to safeguard him from misfortune.

Even in his inscription of the date, Gassan Sadakatsu took care to avoid any possible evil portents by using an alternate character for “Yon” (the number four), instead of the standard character for “Shi” 四, as I have used in the text above (my character set doesn’t seem to have this one he used). The character for “Shi” can mean death, so by avoiding its use, Sadakatsu has preserved the character of this tanto as a talisman against misfortune.

In terms of its construction, this piece is marvellously worked and flawless, showing off all the skills of the master. The yakiba in nie deki is vigorous and full of activity. Following the lines of the kitae, uchinoke and hotsure regularly break free from the hamon, and and it is lined with fine sunagashi and black inazuma. There are long ashi in places, and near the boshi the hataraki combine into nijuba, doubling the hamon.

The tanto is perfect polish, showing off a jihada full of profuse ji nie which cluster into strong chikei. The mune is mitsu, as is typical for this smith. The nakago bears his signature and kao, and though this tanto is unpapered, this signature carries a personal and permanent guarantee of authenticity.

Gassan Sadakatsu works are receiving papers from the NBTHK at this point, and have been graded as high as Tokubetsu Hozon. It is likely that one day in the (far) future, the best of them will be Juyo Token.

In closing, this is a flawless high class work in a beautiful style by one of the representative artists of his time period. It is easily one of my favorites.