Archived Nihonto.ca (Yuhindo.com): Osafune Kanemitsu

Enbun Kanemitsu

| period: | Nambokucho |

| designation: | NBTHK Juyo Token (2005) |

| nakago: | o-suriage, three mekugiana |

| nagasa: | 71cm |

| motohaba: | 3cm |

| sakihaba: | 2.4cm |

| price: | N/A |

There are likely two generations of Kanemitsu, one showing an older style close to his father Kagemitsu, and one showing a style of the late Nambokucho where the sugata is very long, with wide mihaba and O-kissaki.

There is, however, no full agreement about there being two generations of Kanemitsu, as some agree with the theory of one long lived master smith. Fujishiro in particular states:

He was born as the heir son of Kagemitsu, and called Sonzaemon. It is recorded in the Koto Meijin Daizen that he “Was born in Koan Gannen, died in Enbun Gonen at the age of 83”, but there are also works of his dated Enbun Rokunen. Previously, the Kanemitsu of the Enbun era was taken as the nidai, but I think this is a continuation from the shodai Kanemitsu and is the same person.

This one generation / two generation theory often comes about in the case of style changes. The simplest explanation is two smiths, but it is also possible that what seems to be fairly abrupt changes from examples left to us may be one smith changing style during his career for reasons of tactical changes in warfare, or even personal reasons. Consider Inoue Shinkai changing his name midway through his career and changing his style from his school style to one meant to copy Go Yoshihiro. If Inoue Shinkai worked 400 years earlier and left fewer signed pieces due to o-suriage, then we would probably be having the same arguments over one or two generations.

Fujishiro goes on to state that in his opinion, Kanemitsu became the leading smith of the Soshu den. This is an interesting statement given that he is a mainline smith of the Osafune school in Bizen. The Osafune school is the longest lived and most illustrious in the sword world, and Kanemitsu was its head smith during his career.

Dr. Homma Junji of the NBTHK accepts the two generations theory, and states:

The theory that there were two generations of Kanemitsu has come to be commonly accepted in recent years. All sword directories written between the Muromachi and the beginning of the Edo Period say that Kanemitsu has no successor to his smith name. They alaos say he was active from the Gentoku to the Oan Era, but 50 years of active age is too long for one smith.

At the time of Kanemitsu the style popularized by Masamune and the other great smiths of the Soshu den swept like wildfire throughout Japan. Kanemitsu is counted among the Masamune Juttetsu, but because of the change in style happening near the Enbun period, it is not likely he really studied under Masamune. Rather is is possible that he allowed the Soshu style to flavor his native Bizen style and the resulting merger we now call Soden Bizen.

Chogi (Nagayoshi) is another Bizen smith (and peer of Kanemitsu) who is among the Juttetsu and has the reputation of the “least Bizen-like Bizen smith.” Dr. Homma even states that his style is simply Soshu-den. For similar reasons in timeframe, he was probably not one of the legitimate students of Masamune. Dr. Homma is of the opinion that Nagashige, who is the older brother of Chogi was active around 1334, and since his style is also flavored with the Soshu den it is possible that he was one of the direct students of Masamune. He also leaves open the possibility that Nagashige is the early mei of Chogi rather than an older brother. However the truth may be, the existence of Nagashige in the late Kamakura may be the gateway through which Soshu flows into Bizen.

Kanemitsu in the later part of his career (or the second generation depending on which theory you adopt) made massive swords, well over 3 shaku and these have almost all been shortened down to reasonable sizes for use in the Edo period. Of these formerly massive tachi few now retain signatures regardless of the condition of the rest of the sword. The period these from which these derive is centered around Enbun, so these works are often referred to as Enbun Kanemitsu. This shorthand also conveniently gets around the open argument of the work being made by a long lived shodai or a nidai.

On the early style, Fujishiro writes:

The ko-gonome ha is a style that was received from his father Kagemitsu and continued, and also appears in Morishige and Motoshige. This hamon has a little bit of marumi, and is close to Yoshii Bizen. Beside this, there are small pointed gonome, large saka gonome, angular gonome with a bit of midare nado. These styles were not just in the beginning period, but are also seen in his later years.

Among the blades left to us, there is a wide range of quality, from rough looking blades to those that show the finest possible skill in kitae.

Kanemitsu is rated the highest for sharpness, at Sai-jo O-wazamono. His famous swords have names like Ishikiri (Stonecutter) and Kabutowari (Helmetcutter) and were the companion weapons of famous Generals and Daimyo as a result of their legendary sharpness. In this matter, strictly of cutting ability, Kanemitsu has no peer, not even Kotetsu or Kanemoto.

He is one of the representative smiths of the Bizen tradition, and Fujishiro rates him as Sai-jo Saku for highest quality of manufacture.

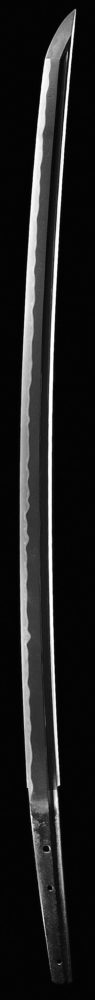

This sword, showing no flaws whatsoever, with beautiful kitae, o-kissaki an active hamon and vivid utsuri shows the style of the Enbun period Kanemitsu works very well. The kitae is remarkably clear, and is work of the greatest skill. This sword represents the top quality of blade made by Kanemitsu, and was part of the important collection of blades from the Museum of Japanese Sword Fittings.

Michihiro Tanobe Sensei Sayagaki

-

… 重要刀剣指定品Juyo Token Shitei HinImportant Sword Designated Article

-

備前國長船兼光Bizen no Kuni Osafune Kanemitsu

-

但大磨上無銘也南北朝期ノ剛壮ナル姿態ヲ呈シ候Tadashi o-suriage mumei nari Nambokucho ji no tsuyoshi takeshi naru sugata tai wo tei shi sourouAlthough shortened and unsigned, the strong and masculine shape shows the period to be Nambokucho.

-

此期同工得意ノ湾主調ノ刃文ヲ燒キKono ki doukou tokui no wan shuchou no ha utsu wo yaki kiThe highlights of the tempering of the ha feature the strong points of Kanemitsu’s work of this period.

-

亦精妙ナル鍛錬ヲ示スナド典型而Mata seimyou naru tanren wo shimesu nado tenki shikashite.As well, the archetypal forging is exquisite.

-

出来宜敷且頗ル健體也Deki mube shiki sharu kentai nari.The workmanship is well founded, moreover is exceedingly healthy.

-

珍々重々Chin chin, cho choIt is greatly prized and treasured.

Bizen Kanemitsu

| period: | Nambokucho |

| designation: | NBTHK Juyo Token (2005) |

| nakago: | o-suriage, three mekugiana |

| nagasa: | 71cm |

| motohaba: | 3cm |

| sakihaba: | 2.4cm |

| price: | -please enquire- |

click here to view the 23 picture slideshow for this sword.

There are likely two generations of Kanemitsu, one showing an older style close to his father Kagemitsu, and one showing a style of the late Nambokucho where the sugata is very long, with wide mihaba and O-kissaki.

There is, however, no full agreement about there being two generations of Kanemitsu, as some agree with the theory of one long lived master smith. Fujishiro in particular states:

He was born as the heir son of Kagemitsu, and called Sonzaemon. It is recorded in the Koto Meijin Daizen that he “Was born in Koan Gannen, died in Enbun Gonen at the age of 83”, but there are also works of his dated Enbun Rokunen. Previously, the Kanemitsu of the Enbun era was taken as the nidai, but I think this is a continuation from the shodai Kanemitsu and is the same person.

This one generation / two generation theory often comes about in the case of style changes. The simplest explanation is two smiths, but it is also possible that what seems to be fairly abrupt changes from examples left to us may be one smith changing style during his career for reasons of tactical changes in warfare, or even personal reasons. Consider Inoue Shinkai changing his name midway through his career and changing his style from his school style to one meant to copy Go Yoshihiro. If Inoue Shinkai worked 400 years earlier and left fewer signed pieces due to o-suriage, then we would probably be having the same arguments over one or two generations.

Fujishiro goes on to state that in his opinion, Kanemitsu became the leading smith of the Soshu den. This is an interesting statement given that he is a mainline smith of the Osafune school in Bizen. The Osafune school is the longest lived and most illustrious in the sword world, and Kanemitsu was its head smith during his career.

Dr. Honma Junji of the NBTHK accepts the two generations theory, and states:

The theory that there were two generations of Kanemitsu has come to be commonly accepted in recent years. All sword directories written between the Muromachi and the beginning of the Edo Period say that Kanemitsu has no successor to his smith name. They alaos say he was active from the Gentoku to the Oan Era, but 50 years of active age is too long for one smith.

At the time of Kanemitsu the style popularized by Masamune and the other great smiths of the Soshu den swept like wildfire throughout Japan. Kanemitsu is counted among the Masamune Juttetsu, but because of the change in style happening near the Enbun period, it is not likely he really studied under Masamune. Rather is is possible that he allowed the Soshu style to flavor his native Bizen style and the resulting merger we now call Soden Bizen.

Chogi (Nagayoshi) is another Bizen smith (and peer of Kanemitsu) who is among the Juttetsu and has the reputation of the “least Bizen-like Bizen smith.” Dr. Honma even states that his style is simply Soshu-den. For similar reasons in timeframe, he was probably not one of the legitimate students of Masamune. Dr. Honma is of the opinion that Nagashige, who is the older brother of Chogi was active around 1334, and since his style is also flavored with the Soshu den it is possible that he was one of the direct students of Masamune. He also leaves open the possibility that Nagashige is the early mei of Chogi rather than an older brother. However the truth may be, the existence of Nagashige in the late Kamakura may be the gateway through which Soshu flows into Bizen.

Kanemitsu in the later part of his career (or the second generation depending on which theory you adopt) made massive swords, well over 3 shaku and these have almost all been shortened down to reasonable sizes for use in the Edo period. Of these formerly massive tachi few now retain signatures regardless of the condition of the rest of the sword. The period these from which these derive is centered around Enbun, so these works are often referred to as Enbun Kanemitsu. This shorthand also conveniently gets around the open argument of the work being made by a long lived shodai or a nidai.

On the early style, Fujishiro writes:

On the early style, Fujishiro writes:

The ko-gonome ha is a style that was received from his father Kagemitsu and continued, and also appears in Morishige and Motoshige. This hamon has a little bit of marumi, and is close to Yoshii Bizen. Beside this, there are small pointed gonome, large saka gonome, angular gonome with a bit of midare nado. These styles were not just in the beginning period, but are also seen in his later years.

Among the blades left to us, there is a wide range of quality, from rough looking blades to those that show the finest possible skill in kitae.

Kanemitsu is rated the highest for sharpness, at Sai-jo O-wazamono. His famous swords have names like Ishikiri (Stonecutter) and Kabutowari (Helmetcutter) and were the companion weapons of famous Generals and Daimyo as a result of their legendary sharpness. In this matter, strictly of cutting ability, Kanemitsu has no peer, not even Kotetsu or Kanemoto.

He is one of the representative smiths of the Bizen tradition, and Fujishiro rates him as Sai-jo Saku for highest quality of manufacture.

This sword, showing no flaws whatsoever, with beautiful kitae, o-kissaki an active hamon and vivid utsuri shows the style of the Enbun period Kanemitsu works very well. The kitae is remarkably clear, and is work of the greatest skill. This sword represents the top quality of blade made by Kanemitsu, and was part of the important collection of blades from the Museum of Japanese Sword Fittings.

I was the submitter to Juyo Token shinsa in 2005, and I have not yet submitted this sword for Tokubetsu Juyo Token consideration. Four mumei swords by Kanemitsu passed Tokubetsu Juyo in 2006, and Kanemitsu is the smith with the greatest number of Tokubetsu Juyo pieces. Because of the outstanding quality of this piece, and the foremost standing of the smith, I believe it is a worthy candidate for Tokubetsu Juyo.

Juyo Token

Juyo Token

Appointed in the 51st Session, 13 October, 2005

Katana, Mumei, Den Kanemitsu

Keijo

Shinogi zukuri, iori mune, wide mihaba, difference between the moto and saki haba is almost not noticeable, sori is shallow, elongated chu-kissaki.

Kitae

Tight ko-itame hada, with very fine ji-nie, fine chikei inserted, and midare utsuri stands out clear and bright.

Hamon

Mainly a ko-gunome tone, with a mixture of ko-choji, kakubaru ha, and togari ha, abundant ko-ashi, yo are mixed in, with abundant ko-nie, there is kinsuji and sunagashi, yubashiri appears here and there, and the nioi-guchi is bright.

Boshi

Midarekomi, saki returns in togari, and is hakikake.

Horimono

Bohi are kakinagashi on the omote and ura.

Nakago

O-suriage, saki is a shallow kurijiri, yasurime is katte sagari, three mekugiana, mumei.

Setsumei

Kanemitsu is the lineage of the eldest son following Kagemitsu of the Osafune Ha. Extant signed pieces span a period of about forty five years from Genko Gannen (1321) at the end of the Kamakura period and extending to Joji in the Nanbokucho period. As for their works, up until around Koei (1342-1345) in the early Nanbokucho period, the sugata was ordinary in the tachi and tanto, and they were tempered with a mixture of gunome in a suguba tone, or with a kata-ochi style of gunome, and overall gave the impression of following the style of the father Kagemitsu, but from around Jowa (1345-1350) to Kano (1352-1352) the style became a large one, a hamon of mainly a notare tone, which had not been seen before, appeared, and this is frequently seen from around Bunna (1352-1356) to Enbun (1356-1361). This katana shows a work style in which, in a kitae that is a tight ko-itame hada, there is very fine ji-nie, fine chikei are inserted, and midare utsuri stands out clear and bright. The hamon is mainly a ko-gunome tone in which ha such as ko-choji, kakubaru ha, and a hint of togari are mixed in, abundant ko-ashi is inserted, yo is mixed in, there is abundant ko-nie. The boshi is midarekomi, and the saki returns in togari, and is a piece which supports the traditions of Kanemitsu. The kitae, without any softness, is exquisite. The yakiba has abundant ko-nie and the nioi-guchi is bright, kinsuji and sunagashi active in fine lines, yubashiri is applied. The ji and ha are superior, and moreover, are very interesting. This is a work that can be judged to be by Kanemitsu.

Michihiro Tanobe Sensei Sayagaki

Michihiro Tanobe Sensei Sayagaki

-

… 重要刀剣指定品Juyo Token Shitei HinImportant Sword Designated Article

-

備前國長船兼光Bizen no Kuni Osafune Kanemitsu

-

但大磨上無銘也南北朝期ノ剛壮ナル姿態ヲ呈シ候Tadashi o-suriage mumei nari Nambokucho ji no tsuyoshi takeshi naru sugata tai wo tei shi sourouAlthough shortened and unsigned, the strong and masculine shape shows the period to be Nambokucho.

-

此期同工得意ノ湾主調ノ刃文ヲ燒キKono ki doukou tokui no wan shuchou no ha utsu wo yaki kiThe highlights of the tempering of the ha feature the strong points of Kanemitsu’s work of this period.

-

亦精妙ナル鍛錬ヲ示スナド典型而Mata seimyou naru tanren wo shimesu nado tenki shikashite.As well, the archetypal forging is exquisite.

-

出来宜敷且頗ル健體也Deki mube shiki sharu kentai nari.The workmanship is well founded, moreover is exceedingly healthy.

-

珍々重々Chin chin, cho choIt is greatly prized and treasured.